What does ‘legal activism’ mean?

Legal activism means using the law (national or international) to advocate for social justice and rights realisation. Legal activism includes litigation and other tools like community, media and policy advocacy, protest and social mobilisation.

Can you tell us a little about the situation of people who use ‘legal activism’?

In South Africa, it is more difficult for poor people, both urban and rural, nationals and non-nationals, to access the formal economy. In order to make a living, people build shacks or occupy buildings near economic opportunities and social networks, working in in the informal economy. Many urban poor people are migrants or refugees and, because of a broken refugee system, they are forced to live here without residents’ permits or official recognition. It is prohibitively expensive for poor people to qualify and navigate onerous administrative systems. As a result, they become excluded from what we call “invited” participatory and accountability mechanisms and resort to self-provision, including to access to water and sanitation services.

So we have a situation where urban poor people may be excluded from services delivery and from mechanisms to engage government to achieve change. Even where people are included in the formal democratic process, local government is unresponsive, and they find themselves knocking on a closed door. People mobilise and engage in protest and even litigation, often as a last resort.

Can you give an example of ‘legal activism’ in practice?

The Marikana informal settlement, home to at least 60,000 people, provides a good example of informal settlement residents employing diverse strategies to secure a home and services near to Cape Town. They eventually litigated against the City of Cape Town to expropriate the land on which they live for housing, and safe reliable water and sanitation will be the result.

Another example is Slovo Park. After 25 years of tireless engagement with the state, including through protest, the local leadership of the Slovo Park informal settlement took the City of Johannesburg to court for trying to evict and relocate them far from their social, cultural and economic life. In 2016 the High Court ordered the City to upgrade their settlement with meaningful community participation. A task team of housing, water, sanitation officials, legal representatives, community leaders and built environment practitioners recently submitted an upgrade plan for funding by provincial housing. It took three years after the judgment, 22 years after the community first mobilised, for the City to provide electricity. It takes immense perseverance, but eventually, the combination of confrontation and collaboration is reaping material benefits.

“Don’t feel defeated if human rights are not in your Constitution.”

What is the role of protest and litigation in legal activism – and what does it entail?

Protest and litigation are often last resort measures, and, like formal methods, are seldom effective unless complemented by other strategies. Litigation should complement and support other strategies already employed by communities like community mobilisation, engagement with government, relationship-building, and protest too where it makes sense. Litigation also helps to mobilise these actions, a phenomenon called “legal mobilisation”.

On protest: communities and groups have increasingly relied on the right to protest to participate politically and to express their dissent. The use of protest is widespread in many countries and has and will continue to rise as communities feel the climate impacts on the availability and quality of water. The main point about protest is that it is meant to be disruptive. Protests take many different forms – from sit ins to blocking freeways – and they are shrouded in many myths. Protests can be individually or collectively organised, they can be directed at government or the private sector or any other actor, they can be confrontational, or they can be co-opted, they can be driven by conservative or by progressive ideological agendas. Protests can even be supported by government officials or politicians to help garner support for actions or budgets in the interests of wide or narrow community groups.

What are the key ingredients for legal activism to be successful?

Community organisation and mobilisation is the driving force behind any form of activism. It is vital to the success of litigation, to meaningful policy engagement, to social change.

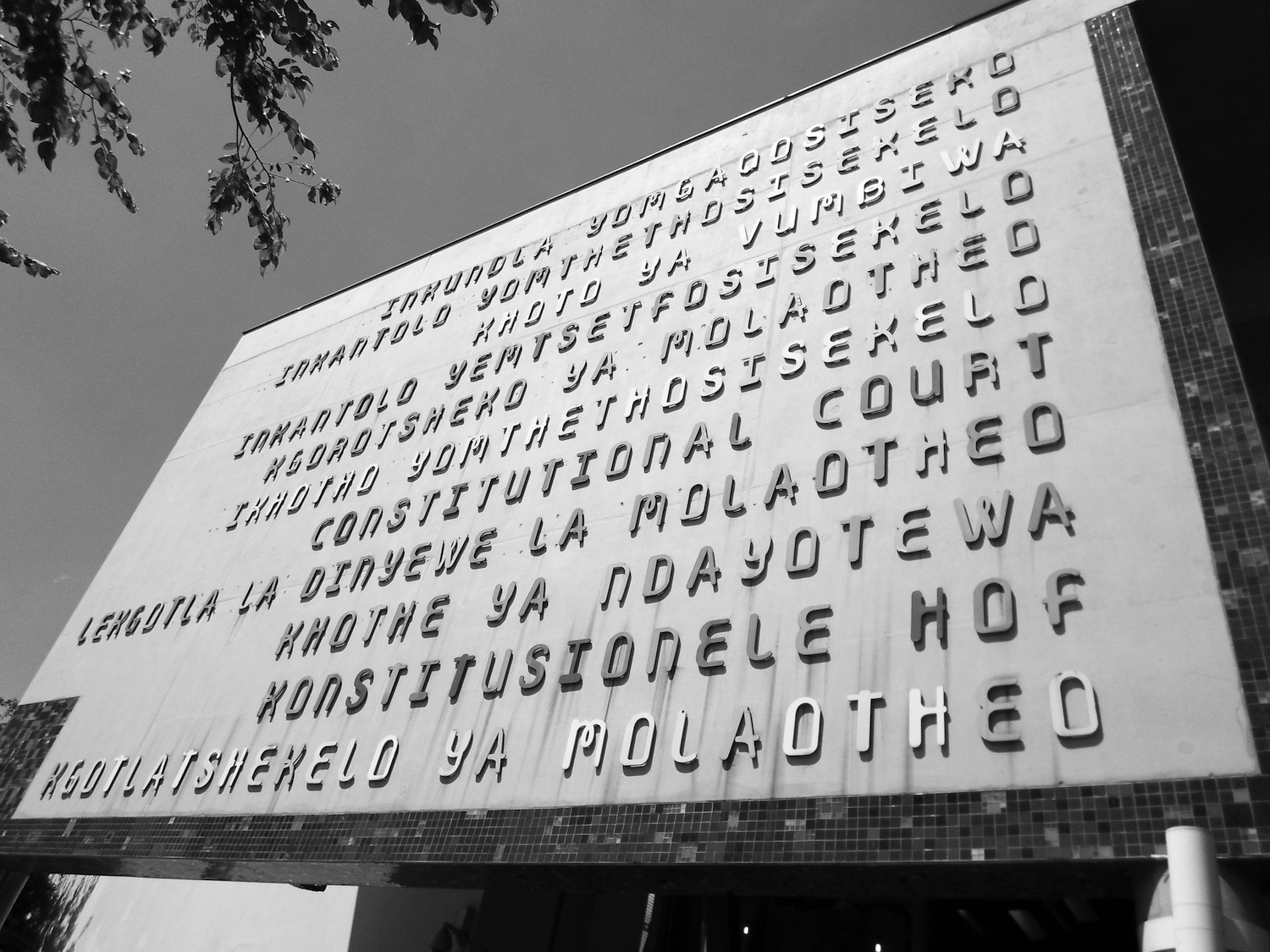

How can you litigate for the rights to water and sanitation when they are not in your Constitution?

If you are creative, you find pieces of local law that are ‘justiciable’ for water and sanitation rights. Don’t feel defeated if human rights are not in your Constitution. Yes, legal reform is possible, yes continue to advocate to domesticate international human rights law using all the invited and formal participatory mechanisms available, and work in parallel with legal NGOs to find strategic opportunities in your procedural law, and in regional and international law. Engage public interest legal organisations in northern or neighbouring countries to lead strategic litigation in your country. Partner with human rights defenders’ networks and environmental justice CSOs. We will never win these battles alone. Don’t give up.