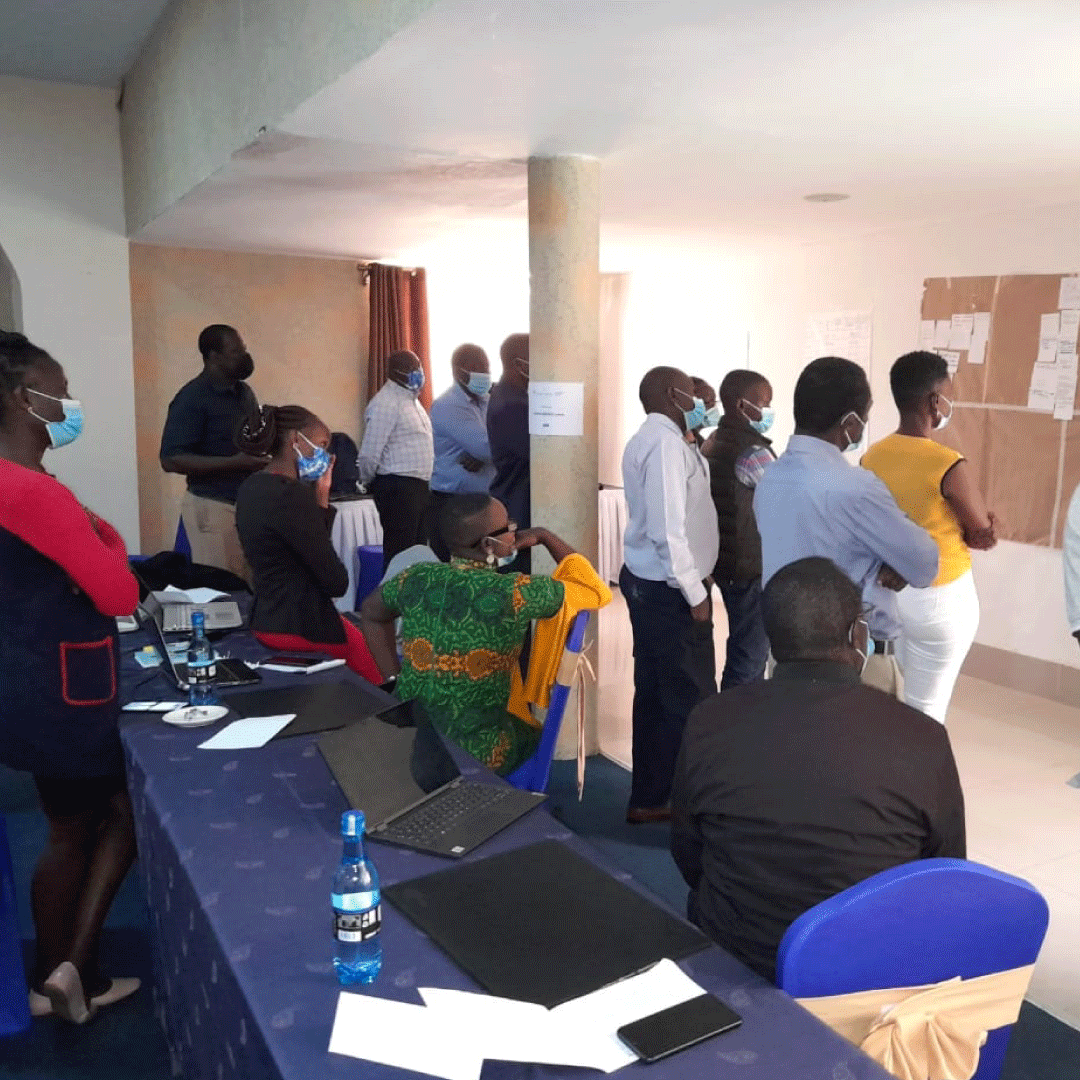

Citizens participate in programme review and planning

People in the WASH sector often say that they work in support of the human rights to water and sanitation when their organisation is active in bringing taps and toilets to unserved communities. Malesi, what do you say to that?

Of course communities are helped when organisations provide services that are not there. However, if we take human rights seriously, then realising services is the duty of the government. So if organisations continue to provide services, they are effectively helping the government turn a blind eye to the service gaps that they should be closing.

Is it easy for organisations to adopt a human rights perspective in their work?

In my experience it depends on where an organisation is coming from. For KEWASNET for instance, it was not difficult to start using human rights at the centre of its work. KEWASNET and many of its members had already had a focus on governance; so quite a bit of language that was being used in governance translated to human rights language.

It is different for organisations that were working as a service delivery institution with the government as a partner. Adopting a human rights perspective, those organisations now had to make people and their needs the centre of their attention. This can be difficult for the position of the organisation, as they are now seen in a different light by the government, which had in the past always treated them as an accompanier rather than an adversary. For such organisations it is more difficult, but definitely possible to include a human rights approach. Change then needs to be introduced more gradually.

For example, the Kenya Water for Health Organisation (KWAHO) has been in the sector in Kenya since 1976 and was an established WASH service provider in urban communities for many years. But today, their portfolio is much more on human rights engagement than on service provision. They gradually changed the way they work and separated their portfolios. KWAHO became more human rights based and is now much more a governance and human rights organisation.

Why is it so important that organisations include a human rights perspective in their work?

An important point is that government is the primary duty bearer, and the only institution that exists everywhere. It’s not perfect of course, but in principle, for every person, every rights holder, there is a responsible government office with the responsibility of realising services. This is not true for civil society organisations. So if government improves the way it works, scale is possible.

Moreover, for the organisations that I know of, working with rights helped shape their approach in programming and delivery through expanding the spaces for citizen participation within projects. Organisational consciousness about the centrality of citizens in the human rights to water and sanitation helps the organisations to be more sensitive to systematic exclusion, and particularly roles they may have played in helping government turn a blind eye on its obligations.

These are important developments.

“For every rights holder, there is a responsible government office with the responsibility of realising services.”

What is stopping organisations from making this transition? What is needed to speed it up?

Finding financial resources is a challenge in the transition from service provision to a human rights based approach, because human rights work is less funded and less lucrative. Donors are reluctant to fund this type of work because progress in human rights work is not always easy to predict and usually not linear. Organisations cannot commit to a donor that at the end of a certain project period, a certain number of water points or sanitation facilities will exist, for instance.

Donors need to understand that working with a human rights perspective is essential for long-term results. KEWASNET and her members have increasingly sought to demonstrate that SDG 6 is largely a conversation about achieving the human rights to water and sanitation for all, hence there is value in funding partners directly investing in human rights work as a way to compel governments to fulfil the ambition of the SDGs.